The Question That Won’t Go Away

Every generation wrestles with this question: If God is truly good, how could He allow anyone to suffer forever? It is asked in grief at funerals, debated in classrooms, and whispered in the quiet of the night.

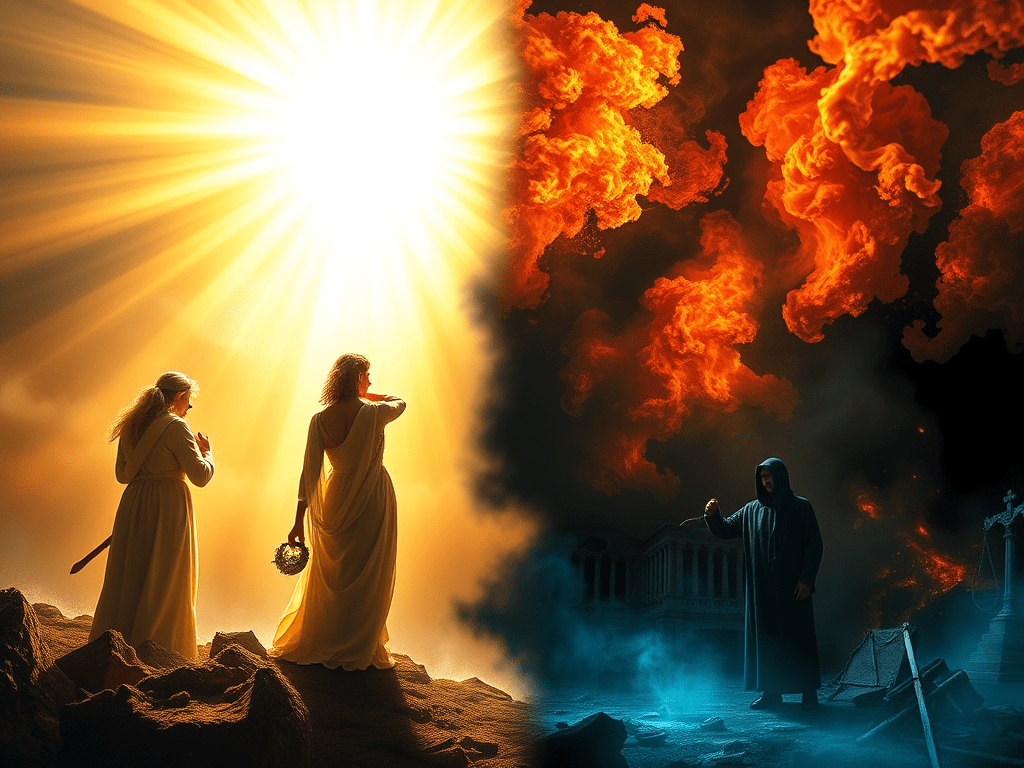

At its core, the question is not only about mercy but about justice. If God is perfectly good, then His goodness must be both merciful and just. Mercy without justice would trivialize sin; justice without mercy would crush hope. The debate over hell is therefore a debate over how God’s goodness expresses itself—through irresistible mercy that eventually reconciles all, or through perfect justice that honors freedom and holds sin accountable forever.

Universalist Answer: Love Wins in the End

One response is universalism—the belief that God’s goodness guarantees that all will eventually be saved. Universalists point to passages such as 1 Timothy 2:4, which declares that God “desires all people to be saved,” and Philippians 2:10–11, which envisions every knee bowing and every tongue confessing. For them, sin and rejection are distortions, not permanent realities. Once deception is stripped away, the will naturally chooses God.

In this view, hell may exist, but only as a temporary place of correction or purification. A good God’s mercy is too strong to let anyone be lost forever. Freedom is not diminished when resistance is overcome; rather, freedom is fulfilled when the will finally embraces truth. To cling to evil forever is not freedom but slavery, and God’s goodness heals the will so it can say “yes.”

Traditional Answer: Goodness Honors Freedom

The traditional position sees things differently. It insists that God’s goodness is precisely why hell exists. Jesus spoke of “eternal punishment” alongside “eternal life” (Matthew 25:46), and Hebrews 9:27 declares that after death comes judgment. Thinkers like Aquinas taught that at death, the soul is no longer subject to change. Freed from bodily passions and time, the will’s orientation—toward or away from God—is revealed and confirmed.

Here, freedom is radical. A good God respects human freedom, even when it leads to eternal rejection. C.S. Lewis captured this with the haunting phrase: “The doors of hell are locked on the inside.” Hell is not God’s cruelty but the tragic consequence of a will eternally turned inward. To override that choice would reduce freedom, and a good God does not coerce.

Freedom: Reduced or Fulfilled?

At the heart of the debate lies the meaning of freedom. Universalists see freedom as the ability to flourish in truth. Once deception is removed, the will naturally aligns with its true end—God Himself. Freedom is fulfilled, not reduced, when resistance collapses.

Traditionalists, however, insist that freedom must include the possibility of eternal irrationality. Pride can cling to autonomy even against reason and mercy. For them, freedom is honored only if the “no” can be eternal. Thus, goodness is expressed either in mercy’s triumph or in freedom’s permanence.

Human Nature and the Good

Universalism assumes that human nature, once healed, will always choose the good. We are made in God’s image, and that image cannot be eternally destroyed.

Traditionalism counters that freedom allows irrational defiance even against one’s true design. Human nature may be oriented toward God, but pride can eternally resist Him. A good God does not erase that possibility, even if it leads to tragedy.

Privation and Eternity

Evil is often defined as privation—a lack of good. Universalists argue that privation cannot be eternal because it has no substance. Lies collapse when confronted with infinite truth.

Traditionalists respond that privation can endure eternally, not as coequal with God, but as derivative—sustained by the will’s refusal. Just as humans exist eternally by God’s sustaining power, so too can privation persist as the tragic consequence of freedom. Eternity can contain both fullness (God’s presence) and emptiness (privation), without making them equal.

Derivative Eternity vs. Divine Eternity

God alone is eternal by nature. Creatures exist eternally only by His sustaining power. Universalists argue that only fullness can be eternal; emptiness must collapse. Traditionalists counter that emptiness can persist eternally, not rivaling God, but parasitic on freedom. Hell’s eternity, then, is derivative, not coequal with God’s eternity.

This distinction allows traditionalists to affirm both God’s supremacy and the possibility of eternal separation. Universalists reject it, insisting that emptiness cannot endure forever in the face of infinite truth.

The Climactic Contrast: Perfect Justice

Here the debate reaches its sharpest edge. Universalists defend their position by redefining justice as restorative rather than retributive. They argue that God’s justice is satisfied when sinners are healed, not when they suffer eternally. Punishment, in their view, is corrective—discipline that leads to repentance. They point to the cross as the place where perfect justice was already carried out, claiming that Christ bore the penalty for all sin, making eternal punishment unnecessary.

But this defense falters under scrutiny. If justice is only restorative, then the seriousness of sin is diminished. If punishment is temporary, then the moral weight of rejecting God is softened. Perfect justice requires more than eventual healing—it requires eternal accountability for eternal defiance. To collapse justice into mercy is to erase the very distinction that makes God’s holiness meaningful.

A courtroom image clarifies the point: imagine a judge who always pardons, no matter the crime. Mercy may be abundant, but justice is absent. The victims are dishonored, the law is mocked, and the gravity of wrongdoing is trivialized. In the same way, if God’s justice is reduced to eventual reconciliation, then sin is never truly answered. A good God must be both merciful and just—and justice without eternal consequence is incomplete.

Thus, the climactic contrast stands:

- Universalists: Perfect justice restores and reconciles all.

- Traditionalists: Perfect justice requires eternal accountability.

To deny eternal consequence is to compromise God’s perfect justice. A God who is truly good must uphold both mercy and justice, not collapse one into the other.

Choose While You Still Can

Would a good God send people to hell? Universalists say no: His goodness ensures that everyone eventually turns to Him. Traditionalists say yes: His goodness honors freedom, even when it leads to eternal separation.

A good God is not less good because He allows hell. He is more good, because He honors the dignity of human freedom. He is more good, because He upholds justice without compromise. He is more good, because He takes sin seriously, refusing to trivialize the weight of rebellion. Mercy is wide, but justice is perfect. Together they reveal a God who is both loving and holy, both compassionate and righteous.

The tension may remain unresolved in theory, but in practice one truth is unavoidable: our choices now matter. If the will is fixed at death, then the decisions we make in this life carry eternal weight. To deny eternal consequence is to compromise God’s perfect justice.

Universalism, for all its appeal, collapses justice into mercy and diminishes the seriousness of sin. It offers comfort, but at the cost of God’s holiness. Hell, by contrast, is the solemn witness that God’s justice is real, that freedom is honored, and that sin is not trivial.

Universalism comforts, but it deceives.

Hell warns, but it tells the truth.

So do not wait. Do not gamble on tomorrow. Do not presume upon mercy while despising justice. Seek truth, embrace goodness, and turn toward God today. His mercy is open, His justice is real, and His goodness is calling you home.